Wednesday 24/11/2021

PHOTO: Alejandra Misiolek

Text: Alejandra Misiolek

In the previous post we explained what ghosting is and we tried to understand where ghosting comes from. In this post we are going talk about breadcrumbing and we will have a closer look at the consequences of both.

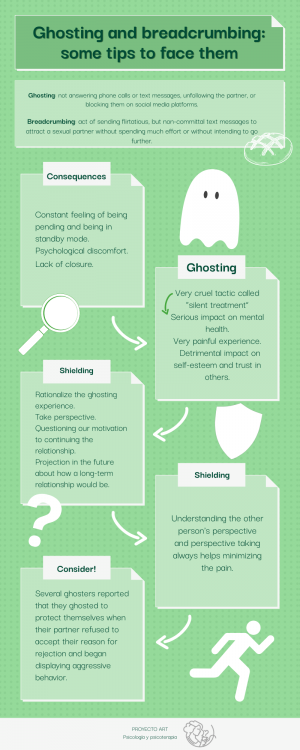

While ghosting refers to not responding to phone calls or text messages, no longer following partners or blocking partners on social network platforms, breadcrumbing is defined as the act of sending out flirtatious, but non-committal text messages (i.e., “breadcrumbs”) to lure a sexual partner without expending much effort or without an intention of ever taking it further.

What breadcrumbers like is attention. So, what they do is flirt here or there, post likes on social networks like Instagram or send texts just frequently enough for receivers to not lose interest in them, but not enough for relationships to develop. Breadcrumbing is not such a clear dissolution strategy as ghosting but rather a way of keeping a date on “hold” where a dynamic is created in which breadcrumbers remain relevant/attractive for others.

Breadcrumbing has not received as much scientific attention as ghosting yet, therefore empirical evidence for breadcrumbing is more limited, however, studies reported that 35.6% of Spanish adults referred to being victims of breadcrumbing.

What are the psychological consequences of ghosting and breadcrumbing?

Although ghosting is a way to end relationships and breadcrumbing is a way to maintain certain relationships for different purposes, what they have in common in terms of affecting people who experience them is a constant feeling of awaiting answers and being placed in a standby mode. This lack of an explicit explanation or declaration causes that the ghosted partner is not aware of what has happened and is left to interpret on their own what the absence of communication might mean. No wonder this lack of closure may generate insecurity in ghosted partners and, as studies show, may cause psychological distress, emotional dysregulation, loneliness, sadness and anxiety and might result in a mindset where individuals come to internalize that there is something fundamentally wrong with them.

The reason why ghosting can have a serious impact on a person’s mental health is because it can be seen as a very cruel tactic called “silent treatment”. “It essentially renders you powerless and leaves you with no opportunity to ask questions or be provided with information that would help you emotionally process the experience. It silences you and prevents you from expressing your emotions and being heard, which is important for maintaining your self-esteem”. (Jennice Vilhauer)

No doubt that this silent rejection called ghosting is a very painful experience and according to research, it literally hurts. Several fMRI studies show that romantic rejection in long-term relationships activates the pain network. Researchers found that even in early dating stages romantic rejection triggers cardiac deceleration. Additionally, research on social rejection showed that especially when the rejection is unexpected, it is associated with activation in brain areas overlapping with the pain network. Other studies show that experiencing ghosting has a detrimental impact on self-esteem and trust in others. This means that when people with low self-esteem go through multiple experiences of ghosting, they might experience the rejection as even more painful because they have fewer natural opioids (painkillers) released into the brain after a rejection compared to people with higher self-esteem.

So, if ghosting is so painful, how can we protect ourselves from suffering its consequences?

1.There are some coping mechanisms that may prevent dating app users from experiencing lowered self-esteem like: rationalizing the ghosting experiencing by arguing it is part of using dating apps; taking perspective and looking at what happened from a broader angle and seeing not only our possible faults but also of the partner; questioning our motivation to continue a relationship with someone who has tendencies of disappearing and making a projection into the future about how a long-term relationship with someone who doesn’t face problems but rather runs away from them, would look like.

2. Research shows that those who had ghosted others were less likely to rate ghosting as painful. This means that having ghosted other dating app users may also serve as a buffer. Why? Because we can understand the other person’s perspective and perspective taking always helps minimize pain.

3. One interesting finding was that several ghosters reported they ghosted to protect themselves as the ghostee refused to accept their reason for rejection and started showing aggressive dating behavior such as repeatedly sending unsolicited messages and stalking behavior. Such findings suggest that some individuals may be more likely to be on the receiving end of ghosting compared to others. Why? Because people who show hostility and aggressive behavior when being rejected are the ones who are more sensitive to rejection because they suffered rejections before (anxious attachment style) and have a lower self-esteem as a consequence. Therefore, if you don’t want to be ghosted, ask yourself how you react to rejection and if there is space for talking openly in the relationship.

In conclusion, ghosting and breadcrumbing can be painful, and we should look for strategies to avoid falling into it and coping with its consequences once it happens. We cannot have control over the partner, but we have certain control over whom we chose (remember the “dark triad”) and how our patterns of relating promote or not a ghosting behavior (are we sensible to rejection?).

Fuentes:

- Bandura, A., & Hall, P. (2018). Albert bandura and social learning theory. Learning Theories For Early Years Practice, 63.

- Freedman, G., Powell, D. N., Le, B., & Williams, K. D. (2019). Ghosting and destiny: Implicit theories of relationships predict beliefs about ghosting. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(3), 905-924.

- Jonason, P. K., Kaźmierczak, I., Campos, A. C., & Davis, M. D. (2021). Leaving without a word: Ghosting and the Dark Triad traits. Acta Psychologica, 220, 103425.

- Koessler, R. B., Kohut, T., Campbell, L., Vazire, S., & Chopik, W. (2019). When your boo becomes a ghost: The association between breakup strategy and breakup role in experiences of relationship dissolution. Collabra: Psychology, 5(1).

- LeFebvre, L. E., Allen, M., Rasner, R. D., Garstad, S., Wilms, A., & Parrish, C. (2019). Ghosting in emerging adults’ romantic relationships: The digital dissolution disappearance strategy. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 39(2), 125-150.

- Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2020). Psychological correlates of ghosting and breadcrumbing experiences: A preliminary study among adults. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(3), 1116.

- Navarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2021). Individual, interpersonal and relationship factors associated with ghosting intention and behaviors in adult relationships: Examining the associations over and above being a recipient of ghosting. Telematics and informatics, 57, 101513.

- Timmermans, E., Hermans, A. M., & Opree, S. J. (2020). Gone with the wind: Exploring mobile daters’ ghosting experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 0265407520970287.