Wednesday 10/6/2020

PHOTO: Image downloaded from https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/well-good/teach-me/100285387/this-is-what-sugar-does-to-your-brain

Text: Alejandra Misiolek Marín

The vicious circles that make it impossible to lose weight – dopamine and leptin.

PART 2

In the previous post I started talking about the role of dopamine in the control of intake. To get a good understanding of how it works, let’s use two examples taken from scientific studies.

Mice that do not synthesize dopamine.

In one study, mice unable to synthesize dopamine were bred in a laboratory. It was observed that these mice starved to death due to lack of motivation to eat. For this reason, it was shown that dopamine plays a very important role in the motivation to eat. Is this only true in mice or in humans as well?

Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s is a disease that causes degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the brain. For this reason, people affected by this disease tend to consume less food. However, when these people receive treatment to improve the functioning of the dopaminergic pathways (with dopamine receptor agonists), they may develop compulsive eating behaviors.

On the other hand, I told you earlier about leptin, the hormone that is part of the homeostatic pathway. This hormone is secreted by adipocytes, which are the cells that accumulate fat. Since obese people have more fat, they secrete more leptin and since high levels of leptin decrease intake, they should be less hungry.

And why is leptin so important?

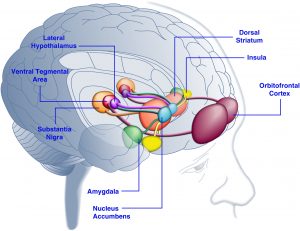

Because it has its receptors in the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) and Substantia Nigra (SN) of the brain, which is where dopamine also has its receptors.

Brain areas involved in the control of intake: Fuente

So, leptin and dopamine, having receptors in the same areas of the brain, are the link between the two pathways of intake regulation.

How do they influence each other?

When leptin receptors in these areas are stimulated, the response of the reward regions to food stimuli decreases. In other words, the more leptin, the less dopamine and the less motivation to eat.

How do we know this is so?

Patients with congenital leptin deficiency (who have no leptin) show increased activation of the dopaminergic system to food stimuli (they are more motivated to eat). On the other hand, leptin treatments consisting of leptin infusions (in VTA – Ventral Tegmental Area) inhibit the activity of dopaminergic neurons and decrease intake, that is, decrease the motivation to eat.

So why does an obese person continue to be motivated to eat?

There is a hypothesis about leptin receptor resistance. This means that, even though they have high leptin levels, intake does not decrease. This resistance could be a consequence of high leptin levels in obese people, which leads to a decrease in signaling sensitivity (a mechanism similar to what occurs in type 2 diabetes).

In this case a situation is created in which we have a lot of leptin that has no effect, since its receptors have lost sensitivity and therefore do not detect it. We could say that the receptors get tired of receiving so much leptin. Let us imagine a situation of absolute silence. Suddenly we hear a noise. To this noise we will react with a lot of alertness. However, when this noise becomes constant and is prolonged over time, we stop noticing it. The same happens with smells, at first, we notice them, but with time we “get used to the smell” and stop perceiving it. These are other examples of how our receptors become exhausted and stop working. So do the leptin receptors in our brain if they receive too much leptin constantly.

And on the other hand, we have dopamine:

Several studies postulate that obese people may not only have resistant leptin receptors, but also suffer from an altered reward system (= dopamine) response.

It was hypothesized and proven through neuroimaging studies (such as Computed Tomography or Magnetic Resonance Imaging), that obesity is related to an increased response of the dopaminergic system to food incentives. Increased activity of reward circuits was observed in obese people while they visualized images of food or thought about food. In contrast, non-obese people showed no such increased activity. This means that, if an obese person sees a donut, the reward circuit is activated more than in a non-obese person. Therefore, the obese person is more motivated to eat the donut than a non-obese person.

In conclusion, hypersensitivity of the reward/dopamine circuit may lead to overconsumption and cause weight gain, while weight gain and obesity may also be caused by resistance of leptin receptors that should modulate dopamine receptors, thus forming a vicious circle. It is a snake that bites its own tail.

The next question to ask is why are the dopamine circuits increased in obese people? Does obesity cause them to be activated or does a person get fat because they are activated? Which came first, the chicken or the egg?

Sources: