Wednesday 18/1/2023

PHOTO: Katarina Wolnik Vera

Text: Alejandra Misiolek and Nicoleta Casangiu

Now that the holidays’ season is over and we are back to our daily routines, with the beginning of the new year there is a certain tendency to take up a new healthy eating habit.

When it comes to healthy eating habits, there’s a whole variety of options and intermittent fasting (IF) is currently one of the world’s most popular health and fitness trends. People fast to lose weight, improve their health and simplify their lifestyles.

Although intermittent fasting is growing in popularity, there are currently few studies that have investigated the benefits and risks of these diets in humans.

What is intermittent fasting?

Intermittent fasting is an eating pattern where people limit their food consumption to certain hours of the day. Intermittent fasting can often be a refreshing alternative for many individuals, in that it does not require people to track calories every day, nor does it forbid individuals from eating certain food groups.

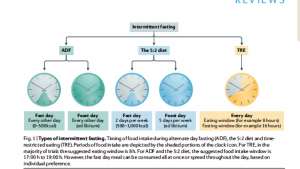

Three types of intermittent fasting have received the most research attention: alternate day fasting (ADF), the 5:2 diet and time- restricted eating (TRE) (Fig. 1). The figure below [1] explains these types of fasting.

What happens when you fast?

During fasting, there is a decrease in insulin levels and an increase in ketone bodies’ production. Those responses could reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, tumorigenesis, and aging. More immediate effects of ketone bodies’ production are enhanced lipolysis, reduced hunger, and improved mental and physical performance (including improved running endurance), which could influence the treatment of obesity. It has been proposed that living species should have mechanisms to adapt to long periods of food deprivation, with a clear metabolic switch from a fed to fasted state, occurring several times a week. In this context, the standard human pattern of three big meals a day, plus snacking, could be maladaptive, maintaining humans in a constant state of increased insulin levels and no ketone bodies’ production. [2]

But is intermittent fasting recommended to everybody? According to scientific reports [1] there is a group of people who could do it and a list of those, for whom it is rather counter indicated.

Who can do intermittent fasting?

- Adolescents with severe obesity (>95th BMI percentile)

- Adults with normal weight, overweight or obesity

- Adults with hypertension and/or dyslipidemia

- Patients with insulin resistance or prediabetes

- Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus or type 2 diabetes Mellitus

Who should not do intermittent fasting?

- Children under the age of 12 years

- Adolescents who are normal weight

- Women who are pregnant or lactating

- Individuals with a history of an eating disorder

- Individuals with a BMI below 18.5 kg/m2

- Individuals over the age of 70 years

However, there are several issues to take into consideration. Clinicians should regularly assess the frequency of adverse effects during the first 3 months and should monitor for deficiencies in circulating levels of vitamins and minerals (such as vitamin D, vitamin B12 and electrolytes). Moreover, patients should participate in structured behavioral change programmed, either in person or online, to help them achieve long-term weight management.

Still, is IF safe for anyone? What are the possible consequences for mental health?

It has been speculated that intermittent fasting could increase the risk of developing an eating disorder.

According to some of the most recent studies on IF and eating disorders, fasting does not increase the rates of binge eating, purgative behavior, depression or fear of becoming overweight. However, in many studies, participants with a history of an eating disorder were excluded. Thus, it remains unknown whether fasting is safe in those with a diagnosed eating disorder.[3]

We could speculate that these regimens are not safe in individuals at risk of developing an eating disorder, such as those with low self-esteem, poor body image, negative affect (a personality variable that involves the experience of negative emotions and poor self- concept), disordered eating behaviors or internalized weight bias, however, the results of such studies are still inconclusive.

In view of the lack of safety data in this area, clinicians should exercise caution when recommending fasting approaches to individuals who might be at risk of developing an eating disorder.

In recent research [3] regarding the association of intermittent fasting implementation with eating disorder symptomatology the results show that intermittent fasters reported heightened level of eating disordered behaviors beyond just fasting and 34.4% of intermittent fasters scored above the clinical cut-off.

While not everyone who fasts develops an eating disorder, fasting is associated with increases in empirically supported risk factors of eating disorder. For example, college women engaging in fasting report greater awareness and internalization of the thin ideal, greater psychological distress, lower self-esteem, and higher engagement in perceived binge eating episodes than do college women who do not fast [3].

In recent research among Canadian adolescents and young adults, results indicate that intermittent fasting is positively associated with eating disorder psychopathology among men, women, and TGNC individuals. Additionally, intermittent fasting was associated with a variety of eating disorder behaviors, the pattern of which varied by gender. Findings underscore that IF may not be an innocuous, pro-health behavior given the clustering with eating disorder behaviors and psychopathology found in this study. Continued research is needed to continue to describe the potential deleterious correlates of IF, and clinical and public health interventions are needed to continue to describe potential harms of IF engagement among the general population.[4]

In studies examining eating disorder severity, fasting was one indicator of greater eating disorder symptom severity among adults with anorexia nervosa [3].

Additionally, studies examining religious fasting suggest that regardless of rationale for fasting, it can contribute to ED symptoms. For example, fasting during Ramadan is associated with heightened eating disorder risk, exacerbation of body image concerns, and preoccupation with food, shape, and weight. [3]

We could conclude that there is a relation between IF and Eating disorders but not necessarily a causal relation. Nevertheless, the findings from these studies have important implications for healthcare and public health professionals. Firstly, healthcare professionals should be cautious when recommending IF regimens to patients who are seeking to lose weight, as this may inadvertently align with eating disorder behaviors and psychopathology. Secondly, given the growing popularity of IF, public health professionals should generate awareness campaigns to provide information on the potentially harmful nature of IF. Furthermore, more scientific studies should be performed to better understand the causal relationship. In other words, what is the chicken and what is the egg in the Intermittent fasting and Eating disorders relationship?

Sources:

- Varady, K. A., Cienfuegos, S., Ezpeleta, M., & Gabel, K. (2022). Clinical application of intermittent fasting for weight loss: progress and future directions. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 18(5), 309-321.

- Bruno Halpern, Thiago Bosco Mendes- Intermittent fasting for obesity and related disorders: unveiling myths, facts, and presumptions in Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2021;65/1

- Kelly Cuccolo, Rachel Kramer, Thomas Petros & McKena Thoennes (2022) Intermittent fasting implementation and association with eating disorder symptomatology, Eating Disorders, 30:5, 471-491, DOI: 10.1080/10640266.2021.1922145

- Kyle T. Ganson, Kelly Cuccolo, Laura Hallward, Jason M. Nagata d-Intermittent fasting: Describing engagement and associations with eating disorder behaviors and psychopathology among Canadian adolescents and young adults in Eating Behaviors 47 (2022) 101681